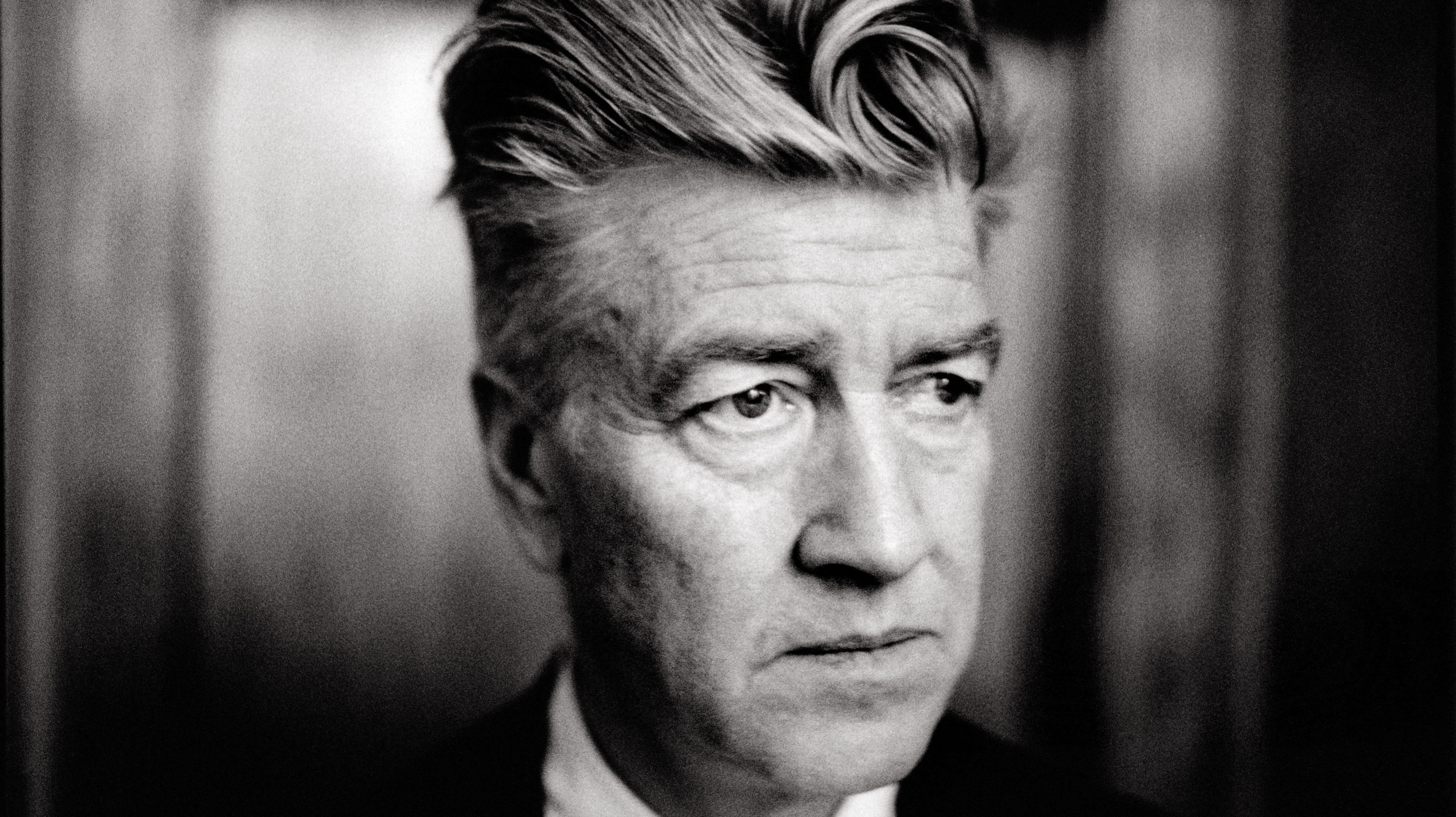

David Lynch and the suffocating rubber clown suit of negativity

/David Lynch—film and television director, painter, photographer, actor, musician—is one of the most creative people I know. (Well, I don’t know him personally, but you know what I mean.) So how does he do all of this? As far as I can tell, it all has something to do with catching fish and not listening to clowns.

Recently, I’ve been trying to put a finger to a feeling. Actually, by doing more of my own work and regularly showing it to people, I’ve been poking that feeling pretty hard. I guess I want to coax it into the light. The feeling lurks behind a lot of what I do. It spoils. It hampers. It says nasty things. I’ve started calling this feeling my little monster, my nightmare, my limit.

David Lynch has another name for that feeling. He calls it—capitalising each word for effect—the “Suffocating Rubber Clown Suit of Negativity.”

In his book, Catching the Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness, and Creativity, Lynch talks about how in 1973 he started meditating in order to deal with persistent negative feelings. Prior to this, he explains:

“I was filled with anxieties and fears. I felt a sense of depression and anger. […] I often took this anger out on my first wife.”

Then after meditating regularly for a few weeks he saw the problem more clearly, and he was able to give those persistent feelings a name:

“I call that depression and anger the Suffocating Rubber Clown Suit of Negativity. It’s suffocating, and the rubber stinks. But once you start meditating and diving within, the clown suit starts to dissolve. You finally realise how putrid was the stink when it starts to go.” (7)

Why a clown suit? I’m not really sure. It certainly fits in with Lynch’s penchant for the disturbing. Maybe too it’s because these days we often associate clowns with something sinister. Perhaps it's because of Stephen King’s Pennywise in his novel It, or the one-handed Mr Jelly in the British TV series Psychoville, or even John Wayne Gacy—the serial killer who dressed as a clown and who just before he was arrested admitted to undercover police officer that “Clowns can get away with murder.”

On top of this, clowns are scary because their appearance feels like an ugly and dysmorphic distortion of human norms: the garish clothes and hair with the saturation turned up full; the over-sized body parts, especially the big red nose and the extra large feet in large shoes; the often conflicting emotions painted large on a blank white face—an over-sized smile beneath mock crying eyes.

(I’m creeping myself out here. I had a picture of a clown above my bed as a kid. I think I’m still working through it.)

Putting a clown face on those nagging feelings while we try our best to go about our lives is perfect because those nagging feelings distort our perspective—they constrict our vision—which reminds me of a quote attributed to Ernest Becker:

“Depression results from cognitively arrested alternatives.”

The same goes for anger and self-loathing too. We become overtaken by negative feelings when we can’t think of a way out of our problems, can’t see any other possibilities to transform our view, which is why we should be wary when the ‘circus comes to town.’

Listen to the work, not the worry

Negative self-talk gets in the way. Like Lynch says:

Anger and depression and sorrow are beautiful things in a story, but they’re like poison to the filmmaker or artist. They’re like a vice grip on creativity. If you’re in that grip, you can hardly get out of bed, much less experience the flow of creativity and ideas. You must have clarity to create. You have to be able to catch ideas.” (7-8)

For Lynch, being creative is like trying to catch a fish, requiring the same patience and stick-to-it-ness as it does to catch real fish.

The basic idea is that when he begins a new project, it is often based around a single idea, often only one fragment. He may not have any idea what the fragment means, but there will be something there that intrigues him. From there, he works on that idea and watches where it takes him. As he explains:

"An idea is a thought. It's a thought that holds more than you think it does when you receive it. [...] It would be great if the entire film came all at once. But it comes, for me, in fragments. That first fragment is like the Rosetta Stone. It’s the piece of the puzzle that indicates the rest. It’s a hopeful puzzle piece." (23)

For Lynch, just that one fragment, if it’s treated carefully, is enough to sustain an entire work. As he explains:

"The idea is the whole thing. If you stay true to the idea, it tells you everything you need to know, really. You just keep working to make it look like that idea looked, feel like it felt, sound like it sounded, and be the way it was. And it’s weird, because when you veer off, you sort of know it. You know when you’re doing something that is not correct because it feels incorrect. It says, ‘No, no; this isn’t like the idea said it.’ And when you’re getting into it the correct way, it feels correct. It’s an intuition: You feel-think your way through. You start one place, and as you go, it gets more and more finely tuned. But all along it’s the idea talking. At some point, it feels correct to you. And you hope that it feels somewhat correct to others." (83)

It reminds me of something John Steinbeck once said:

“Ideas are like rabbits. You get a couple and learn how to handle them, and pretty soon you have a dozen.”

Which is almost identical to what Lynch says, substituting fish for rabbits:

"The beautiful thing is that when you catch one fish, even if it’s a little fish—a fragment of an idea—that fish will draw in other fish, and they’ll hook onto it. Then you’re on your way. Soon there are more and more fragments, and the whole thing emerges."

But the trick for me, and for a lot of people I guess, is to get into a space where you can do your work unhindered by preemptive feelings of shame.

To be able to listen and give full attention to the work, not the worry.

As Lynch remarks in Chris Rodley's book of interviews with the director, Lynch on Lynch:

“What makes you worry about things […] is when you start thinking about what certain people might say about it later. Because you’re not really sure what they might say. And if you start worrying, you could make some really strange decisions based upon that worry. The work isn’t talking to you any more: the worry is talking to you. And you become paralysed. So the trick is: You’ve got to forget making a hero or a fool of yourself and just try to get into that world. And if you can do that, and you feel good about the decisions that you make, then you can weather whatever good or bad storm comes along.” (179)

So, I guess if you could turn this all into a catchphrase, or motto in Latin, it would be something like: Carpe diem, carpe carpum. Cave maccus. Seize the day, seize the fish. Beware the clown.

And in the future, for me—I do like the idea that every time I have a negative thought I should add a comic sound to it.

(Pfft, nice ending! So clumsy)

(Honka. Honka.)

Rabbit

You might also like,Rabbit Hole #17—Five things you might not know about David Lynch.

Painter Tracey Read talks about spending four weeks painting and drawing her way around Italy.