Saddam's Poetry

/Words and cover illustration by Ant Gray

Just before his execution, Saddam Hussein wrote a poem. This wasn’t the first time he had committed an act of literature. Saddam was already a published novelist.

Speaking of dictators…

By August 1939, Germany had already taken over Austria and Czechoslovakia, and now its troops were massing at the Polish border. Europe held its breath.

Britain’s ambassador to Germany, Neville Henderson, was hastily sent to Berlin. His instructions were simple: make it clear that if Germany invaded Poland, Britain and France would declare war. During their negotiations, Ambassador Henderson was surprised how calm the Führer was, despite the fact that their respective countries were about to jump off a cliff.

“I am an artist and not a politician,” Hitler tried to reassure the Ambassador. “Once the Polish question is settled, I want to end my life as an artist.”

In his youth, Hitler had applied twice to an art school in Vienna and was twice rejected. His examiners thought he had a certain level of skill, but thought it was strange that the young artist had a tendency to paint lots of pictures of buildings and cityscapes with no people in them. They encouraged him to be an architect, but Hitler ignored their advice.

A World War and some 60 million casualties after Germany’s invasion of Poland, one of the characters in Mel Brook’s film The Producers—proclaims loudly:

“Hitler—there was a painter! He could paint an entire apartment in one afternoon! Two coats!”

Flash forward to 2003, and US forces discover Saddam Hussein hiding in a six-foot deep cellar only big enough for the recently deposed dictator to lie down in.

He would spend the next three years in a Bagdad detention centre. Towards the end of his life, he occupied his time tending a small garden next to his cell and by, of all things, writing poetry. “Hussein even made gifts of his poetry to his American captors,” an article in Spiegel reported, adding that poetry was “so often his source of solace in times of difficulty.”

That Saddam wrote poetry is fascinating to me. A man who is suspected of having ordered the torture and execution of an estimated 200, 000 of his own people, not to mention all of those who died as a result of his conflicts. A dictator, the New York Times reported, who was fond of saying in meetings with his deputies:

“If there is a person, then there is a problem. If there is no person, then there is no problem.”

But why is it so weird that he wrote poetry? Maybe it’s because, so far, Rabbit Hole has been about how creativity and self-expression are a great panacea. “The liberal arts humanises character and permits it not to be cruel,” the Roman poet Ovid said.

So what, if anything, can be learned from the fact that Saddam wrote poetry and Hitler wanted to paint?

Don’t cry for me Iraq-gentina

Saddam Hussien’s last poem, “Unbind it”, was written just a few days before his execution.

Unbind your soul. It is my soul mate and you are my soul’s beloved.

No house could have sheltered my heart as you have

(Ok. So far, nothing strange.)

If I were that house, you would be its dew

(The dew of the house? Do houses have dew?)

You are the soothing breeze

My soul is made fresh by you

(Is the ‘you’ in this poem the people of Iraq?)

And our Ba’ath Party blossoms like a branch turns green.

(We’re having a what-party now? Oh, sorry. No, I get it.)

The medicine does not cure the ailing but the white rose does.

(Is that stolen from Pink Floyd?)

The enemies set their plans and traps

And proceeded despite the fact they are all faulty.

(Ok, Saddam, getting a bit weird. Let’s skip ahead…)

The enemies forced strangers into our sea

And he who serves them will be made to weep.

(Alright. I’ma stop you there.)

The rest of “Unbind it” is exactly what you’d expect from your average ex-dictator. It’s angry, hurt, self-aggrandising—the kind of poetry you write as a teenager after a painful break-up with someone who everyone else could see was totally wrong for you, but you were attracted to like a fork to a power socket. But instead of being about Angeline or Mark or whoever, it’s about a country—the country you dominated for 24 years through enforced servitude, torture, intimidation and murder.

In another poem Saddam writes:

Dear nation: Get rid of the hatred, take the clothes of hate and throw it into the ocean of hatred,

God will save you and you will start a clean life, with a clean heart.

(Oh, and Iraq—did I leave my Megadeath t-shirt at your place? I can’t find it.)

Sitting in his cell, writing lovelorn poetry to himself and the people of Iraq wasn’t the first time Saddam had dabbled in literature. While he was President, Saddam had written and published four novels.

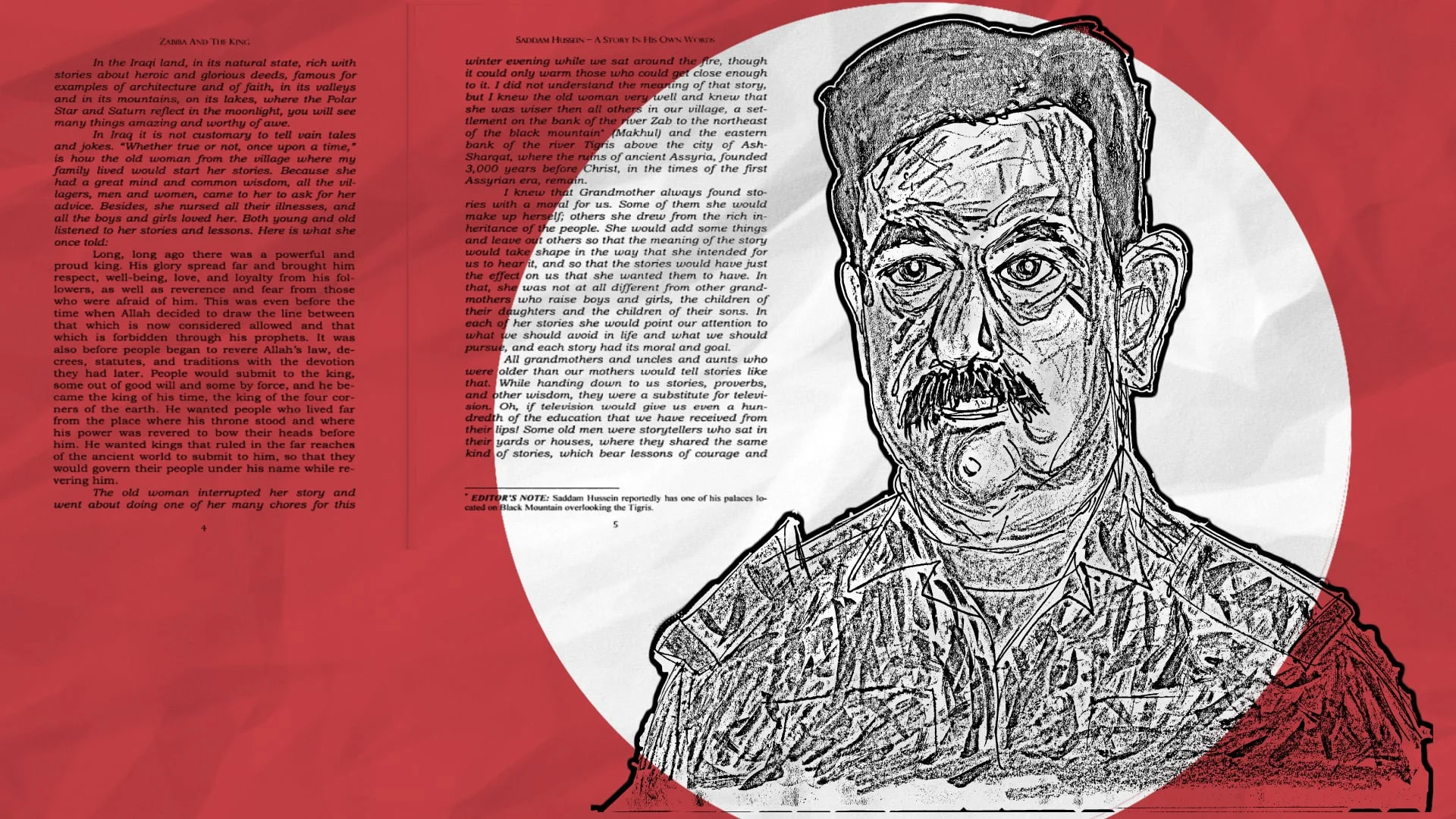

His first novel was Zabiba and the King—a romance written in the style of The Arabian Nights. The book’s main plot is organised around the platonic relationship between Zabiba—a commoner who is married to a brute—and “a powerful and proud king.” A king whose “glory spread far and brought him respect, well-being, love, and loyalty from his followers, as well as reverence and fear from those who were afraid of him.”

Sound like anyone?

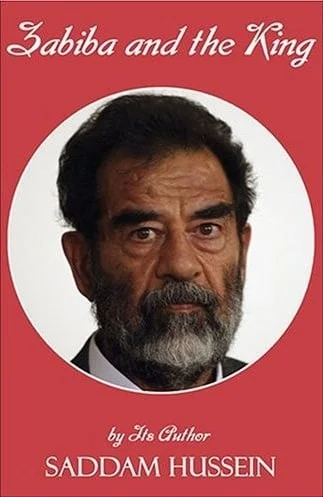

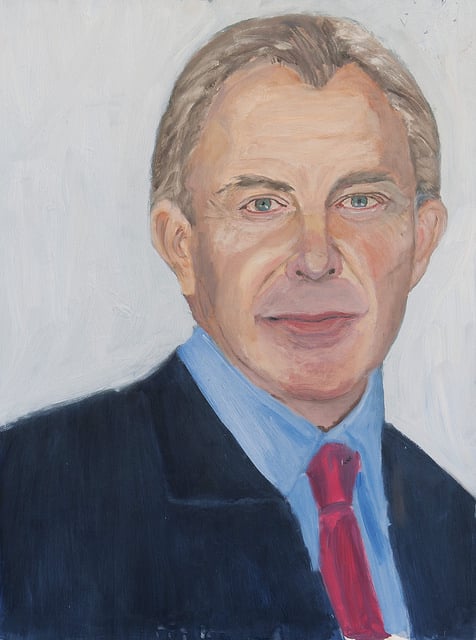

The English language version of Zabiba with post-arrest Saddam on the cover

The King is Saddam and Zabiba stands in for the Iraqi people. Using the same sense of subtlety he evinced by his leadership, the peak of the drama happens when Zabiba is raped by her cruel husband; an event that takes place in the chronology of the novel on January 17—the same date as the start of the 1991 Gulf War between Iraq and the US.

Then, after leading an army in defence of her King, Zabiba is fatally wounded. On her deathbed she advises him:

“You need to be the leader of the people and the army, their guide to virtue, reconstruction, and victory. […] Then the people and its army under your leadership can do the deeds which will bring glory to our country and the one who rules it, and they will become the builders of the glorious history of our great nation.”

(Blegggggghhh! Yikes.)

Zabiba and the King was first published anonymously, but it must have been the worst kept secret in Iraq. It was an overnight sensation, selling over one million copies and eventually being turned into a musical and a twenty-part mini-series for Iraqi TV.

The CIA studied the novel very closely to see what clues it might give about its author. I have this image of a book club meeting in the bowels of the CIA with highly trained analysts sitting around drinking chardonnay and saying things like, ‘I think what Saddam is really trying to say is…’ and ‘I don’t know, I really liked it.’

As Daniel Kalder says in his article titled, “Saddam Hussein tortured metaphors, too”:

“Some critics have suggested that Zabiba and the King was ghostwritten. I doubt that: it is so poorly structured and dull that it has the whiff of dictatorial authenticity. […] And as the butcher of the Kurds outlines the attributes of a good leader (wise, kind, humble, close to the people) it’s interesting to speculate: was this how he perceived himself? I suspect it is. Few among us consciously believe we are wicked. When Saddam did evil he probably told himself it was for the greater good. Dictators, like the rest of us, have an infinite capacity for self-deception.”

Saddam ‘anonymously’ wrote and published another three novels: The Fortified Castle, a 700-page story about a war hero and his Kurdish bride to be; Men and the City, a novel about Ba’ath Party and his hometown of Tikrit; and Begone, Demons, a religious conspiracy novel pitting ‘Zionists’ and Christians against Arabs and Muslims.

Hussein in the Membrane

The fact that Saddam had literary pretensions is reproduced by journalists and commentators in an ‘emperor has no clothes’ kind of way. It becomes further evidence of Saddam’s delusions of grandeur: an opportunity to peek behind the curtain and see the little man pushing buttons and pulling levers, trying desperately to keep up the ‘god-like’ pretense; a chance to peer behind Vader’s mask to see the wheezing geriatric beneath.

At the same time, I see his bad poetry and clunky allegories as a crude defence against vulnerability—something we’re all prone to at times.

I usually don’t like making fun of anybody’s attempts to express themselves or make something, but it’s kind of reassuring that none of us are immune from that vulnerability, even someone as out of proportion and cruel as Saddam Hussein.

Saddam writing poetry and prose is more than a curious quirk of history. To think of him only in terms of his wars and the number of people he tortured and killed inflates him, making him this great inhuman monster. But talking about his awful poetry brings him down to size. In his last days in captivity—his army defeated for a second time and his country under occupation, his rule ended, his sons killed by US forces, his dynasty crushed—and in his darkest hour he does what most of us would: he writes awful, fumbling poetry.

Roll up, roll up. See the President’s doodle

In 2013 a Romanian hacker and unemployed taxi driver, operating under the pseudonym Guccifer, hacked the email accounts of a number of US government officials.

Before he was arrested by Romanian intelligence, Guccifer—as in the name of the designer brand and Lucifer mixed together—published potentially embarrassing emails, images and documents, including a bunch of doodles drawn by former President Bill Clinton. One image he released was a drawing of a limousine on White House letterhead; another image was a briefing document the President had scribbled on during a meeting about Slobodan Milosevic.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

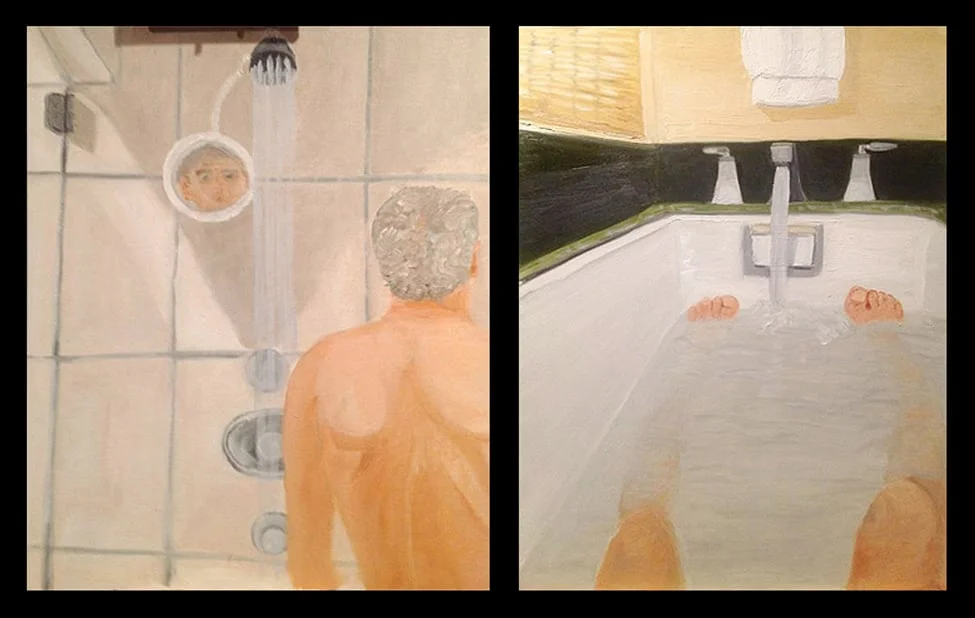

Guccifer, who’s real name is Marcel Lehel, also later released two images that President George W. Bush had sent to his sister via email. They were of two self-portraits he had painted—one of himself in the bath and another one of him in the shower.

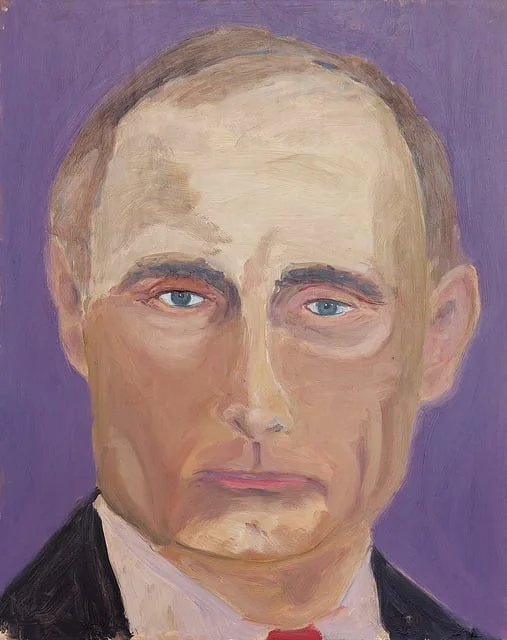

Although angry at the invasion of privacy, Bush eventually declared his love of painting and exhibited his portraits of fellow world leaders—portraits that included his father George Bush Snr., Tony Blair, Vladimir Putin, Angela Merkel and John Howard among others.

Many art critics described his paintings as ‘dreary’ and ‘uninteresting.’ Some were more kind. Bill Arning, director of the Contemporary Arts Museum in Houston, remarked that, “If I walked into some Chelsea gallery and saw this as a precocious 24-year-old Yale graduate and saw these paintings, I’d say: ‘Oh, this is an interesting take on portraiture’.”

(Actually, I love Bush’s bath and shower pictures. And his picture of Putin.)

Arning also had some advice for George W. on how he could improve, suggesting he rely less on using photographs of his subjects as a reference:

“I think he’d be well advised to work from other, multiple photographic sources or the real person to get a little bit more liveliness going on. As soon as you work from a found photo there is a deadening effect. Some artists use this as part of the subject matter, but I don’t think that’s the intention here.”

(I’m sure George W. could get Russian President Vladimir Putin to sit for him. I bet he’s really, really good at sitting perfectly still.)

It’s funny to think of George W. and Saddam, two nemeses at the end of their political lives, pursing creative hobbies. And it makes me feel sorry for Saddam again in a new way. Everyone’s got helpful feedback for Dubya, but none for him.

While Saddam was still in power, Mark Bowden wrote in an essay for the Atlantic entitled, “Tales of the Tyrant”:

“Before publishing the books Saddam distributes them quietly to professional writers in Iraq for comments and suggestions. No one dares to be candid—the writing is said to be woefully amateurish, marred by a stern pedantic strain—but everyone tries to be helpful, sending him gentle suggestions for minor improvements.”

That’s what sucks about being a dictator. It’s so isolating. Why would anyone not having a death wish want to give feedback to a tyrant? And so tryant’s end is often lonely and ridiculous. They’re not used to bobbing up and down on the waves of other people’s opinions; they’re used to telling people what their opinions are.

And probably the same is true of Presidents as well, though George W. seems to have a more realistic view of his own capabilities. When The Dallas Morning News asked about him about his new hobby, he replied:

“People are surprised", the President said. "Of course, some people are surprised I can even read.”

Ant Gray

Painter Tracey Read talks about spending four weeks painting and drawing her way around Italy.